Blog: How to recognize microaggressions

Death by 1000 papercuts: How to recognize microaggressions and what we can do about them

A few of the speakers at The WIT Network International Women's Day Conference brought up microaggression as a critical challenge we are still working to overcome in workplaces. We seem, in general, to be getting better with diminishing macro-aggressions—the loud, outward actions of inequity. Likely because they are easier to recognize and name. However, microaggressions are still affecting corporate cultures and our ability to build truly diverse, equitable teams where individuals feel included: that they belong.

What are microaggressions?

According to Dr. Derald Wing Sue, microaggressions are the everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, which communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to target persons based solely upon their marginalized group membership. (Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation, 2010).

Cherilynn Castleman, Managing Partner at CGI, defines them as off-the-cuff comments that reflect assumptions about what people think about our identity. Sometimes they can come across as a compliment, or they might come across as genuine curiosity.

The American Bar Association states: Microaggressions can be manifested through remarks that are perceived to be sexist, racist, odious, or offensive to a marginalized social group. These negative remarks can have a profoundly negative effect by diminishing the value and humanity of an individual and/or group. In the workplace, this can negatively impact work performance and team dynamics. Microaggressions also can have a detrimental impact on customers and clients, hence dwindling the potential of successful customer service and engagement.[i]

Microaggressions are real, and they impact work culture

As Cherilynn Castleman explained during The WIT Network International Women's Day Talk SOAR Above Microaggressions, to think of a papercut, one that’s deep and hurts like hell, but you can’t see it. That’s what a microaggression feels like. And it can be death by a thousand papercuts.

To paint a picture of how easily a microaggression can slip into conversation, Castleman shares an experience that hurt her deeply: Earlier in my career, I was sitting at our annual sales kick-off dinner with five guys. The head of sales was bragging about how his son was going off to Duke, and his younger daughter was going to apply to a liberal arts college. He turned to the guy next to him and said, Hey Bob, where are your kids going to college? Then he says, Hey Jim, where are your kids going to college? He goes around the table and asks all five guys, where are your kids going to college?

He turns to me and says, Hey Cherilynn, do you think your kids will go to college?

That was like I had been sucker-punched. Did I think my kids would go to college?

Castleman explains that she got very emotional and boasted of her children’s achievements (both of whom are highly educated and very successful). The head of sales got very embarrassed and went to the company’s president with complaints against her character. The company president admonished Castleman for not playing well with the boys.

While she admits she mishandled the incident, claiming that she did not soar above that microaggression, so too was the company president in the wrong for his response to the situation. Castleman’s emotions were real; his response should have been real.

With more clarity, Castleman says she should not have embarrassed the head of sales and instead gone to him privately and dealt with the situation by asking for clarification. Can you tell me more about where you got the idea that African American children don’t go to college? Why ask me, ‘do you think your kids will go to college’ when you asked everyone else where their kids were going to college?

With that response, the microaggression could have been addressed, and the thought process interrupted without embarrassing the head of sales. Then, they could have moved forward with their working relationship.

Addressing microaggressions

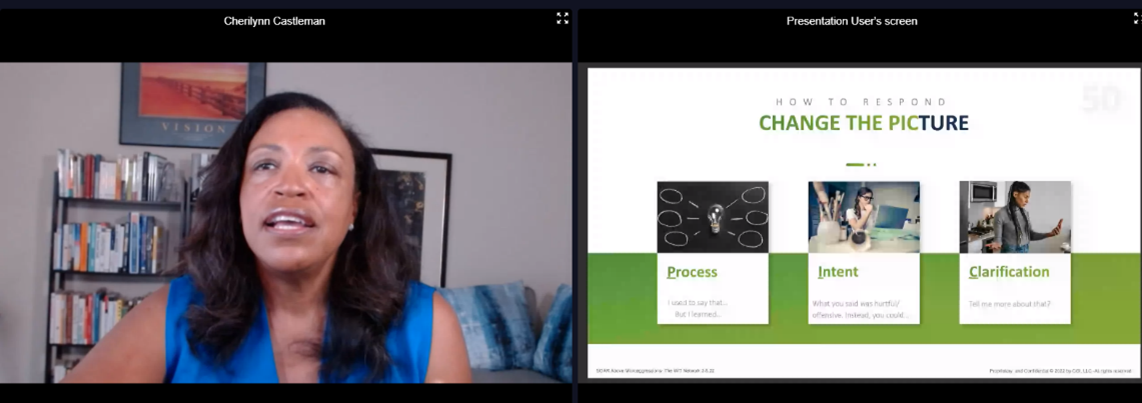

Castleman outlined three ways to approach discussing microaggressions in the workplace.

#1 Process

Process discusses your learning about the necessary change. For example, I used to say but now I say and give a reason.

#2 Intent

Often microaggression isn’t said with the intent to be harmful; it comes from unconscious bias or ignorance. So, addressing the intent behind the statement with the person is essential. I don’t think you meant to hurt me, but what you said was hurtful/offensive. Instead, you could say

#3 Clarification

Asking for clarification gives the other person time to think and consider their words: Tell me more about

If it is safe to do so, microaggressions should be challenged when they occur. That presents a better opportunity to learn and engage. While you want to call out the microaggression, you want to avoid blaming and shaming as that tends to break down instead of encouraging communications.

Microaggressions are real and harmful. The emotions of those on the receiving end are real. Our responses to microaggressions need to be real. Let’s become upstanders, not bystanders.

Watch the ondemand recording of Castleman’s talk to get insight and tips to help you S.O.A.R. above microaggressions.